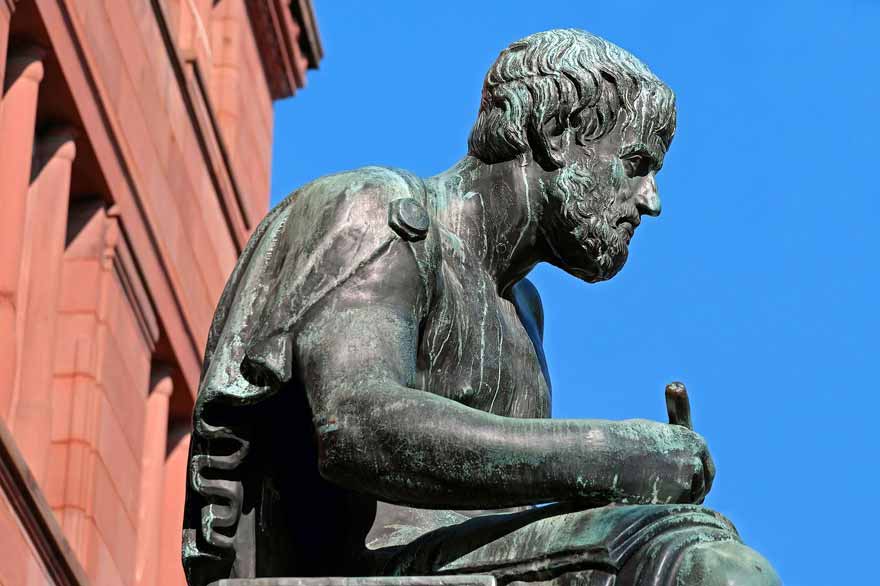

Aristotle, an intellectual luminary of antiquity, left an indelible mark on the annals of human thought. Born in 384 B.C. amidst the scenic landscapes of Stageira in Macedonia, his genesis unfolds against the backdrop of intellectual richness. Aristotle’s inventions, progenitor, Nicomachus, occupied the esteemed position of court physician to the monarch of Macedonia. This familial association potentially paved the way for Aristotle’s early immersion in the realms of biology and medicine. It is plausible that the seeds of his later groundbreaking contributions were sown in the fertile soil of his paternal lineage, a testament to the intergenerational transfer of intellectual vigor. In this article, I am going to compile a short description of Aristotle’s contribution.

Aristotle’s Formative Years at Plato’s Academy

Aristotle’s intellectual journey attained its early zenith within the hallowed precincts of Plato’s Academy in Athens, a crucible of philosophical ferment during his formative years. In the vibrant crucible of academic pursuit, Aristotle emerged as a stellar disciple, distinguishing himself through the acuity of his intellect and the depth of his scholarly pursuits. The Academy, under the tutelage of the eminent Plato, became the crucible in which Aristotle’s intellectual mettle was honed, and the foundation of his seminal ideas in diverse fields was laid.

Aristotle’s Pioneering Contributions to Atomic Theory

Among Aristotle’s multifaceted contributions, his foray into atomic theory stands as a pinnacle of intellectual achievement. The labyrinthine corridors of his mind navigated the intricacies of matter and substance, paving the way for a nuanced understanding of the elemental building blocks of existence. Aristotle’s conceptualization of atoms, although distinct from the later atomic theories, marked an epochal departure from prevailing wisdom, laying the groundwork for subsequent scientific discourse.

30 Great Aristotle’s Inventions and Contributions

The legacy of Aristotle’s intellectual bequest extends far beyond the confines of his era. His groundbreaking ideas resonate across centuries, shaping the contours of philosophy, science, and myriad disciplines. Aristotle’s oeuvre, rooted in the fertile soil of his diverse experiences and erudition, continues to reverberate through the corridors of academia and intellectual discourse. In paying homage to Aristotle, we acknowledge not merely a historical figure but an architect of thought, whose intellectual edifice stands as a testament to the timeless pursuit of knowledge. Find below a synopsis of Aristotle’s inventions:

1. His areas of interest and contribution

Aristotle, the luminary of ancient Greek philosophy, delved into a kaleidoscope of disciplines, imprinting his intellectual footprint across an astonishing array of subjects. His scholarly curiosity and prolific output traversed the realms of logic, metaphysics, mathematics, physics, biology, botany, ethics, politics, agriculture, medicine, dance, and theatre. Within the vast tapestry of Aristotle’s intellectual pursuits, one finds a mosaic of Main Interests, a symphony that includes Biology, Zoology, Psychology, Physics, Metaphysics, Logic, Ethics, Rhetoric, Aesthetics, Music, Poetry, Economics, Politics, and Government. His pen danced across the parchment, weaving treatises that not only encapsulated the essence of these domains but also laid the foundation for future philosophical discourse.

2. Empiricism

At the heart of Aristotle’s ideological revolution lies the epochal concept of empiricism, a paradigm shift that resounds through the corridors of philosophical inquiry. This seismic transformation hinges on the notion that information and knowledge are rooted in empirical experiences, proclaiming, “There is nothing in the mind that has not been in the senses before.”

In Aristotle’s conceptualization, empiricism becomes the lodestar guiding the exploration of truth—a belief that philosophy and science should be anchored in the crucible of experience, where perception and insensible knowledge converge. This incisive perspective on empiricism stands as one of Aristotle’s enduring contributions, a beacon that illuminates the path of knowledge with the radiance of sensory observation.

3. Metaphysics

The enigmatic realm of metaphysics, a term possibly coined by an astute editor in the first century AD, unfolds as a captivating intellectual landscape shaped by Aristotle’s profound insights. Within this metaphysical tapestry, Aristotle designates his magnum opus as the “first philosophy,” elevating it above arithmetic and pure science (physics). This contemplative philosophy, labeled “theological,” embarks on a quest to fathom the divine, charting an intricate course through the esoteric corridors of existence.

Aristotle, the metaphysician par excellence, propounds a taxonomy of causes that underpin the intricacies of change. Material causes, arising from an object’s composition; formal causes, born of its design; efficient causes, stemming from a creator’s agency; and final causes, entwined with a thing’s destiny—these facets of causality weave a rich tapestry of metaphysical exploration under Aristotle’s erudite gaze.

Change, in Aristotle’s metaphysical vista, emerges as both natural and necessary, a cosmic ballet orchestrated by these four distinct types of causes. Each cause contributes harmoniously to elucidate the dynamic processes that define the universe, affirming Aristotle’s enduring legacy as a metaphysical maestro who unveiled the veiled mysteries of existence.

- Change is natural and needed. Four completely different sorts of causes clarify the method of change:

- Material Causes – resulting from what an object is a product of.

- Formal Causes – resulting from an object’s design.

- Efficient Causes – resulting from a factor’s maker

- Final Causes – involving the top in the direction of which a factor is destined.

4. Epistemology

Epistemology, the profound exploration of knowledge and its acquisition posits that the most reliable fount of information emanates from the senses and direct experience. This philosophical stance venerates facts, elevating them to a pedestal above the speculative edifice of theories. The tenet insists on the primacy of empirical evidence, where the tangible and the experiential coalesce into a tapestry of verifiable truths. In this epistemological landscape, the empirical reigns supreme, guiding the seeker of knowledge through the labyrinth of sensory perception and firsthand observation.

5. Mathematical Objects

Embarking on an odyssey through Aristotle’s contemplation of mathematical objects unveils a lexicon of five pivotal concepts that form the bedrock of his discourse. The nuanced terminology includes ‘abstraction,’ a process of ‘taking away’ or ‘subtraction’ (aphairesis), ‘precision’ (akribeia) as a hallmark of mathematical discourse, ‘as separated’ (hôs kekhôrismenon) denoting distinctness, ‘qua’ or ‘in the respect that’ (hêi) illuminating the contextual relevance, and ‘intelligible matter’ (noêtikê hylê) that encapsulates the essence of the abstract. This intricate tapestry weaves together Aristotle’s contemplation, transcending the mundane to delve into the metaphysical underpinnings of mathematical entities.

6. The Logic of the Categorical Syllogism

Navigating the labyrinthine corridors of logical deduction, the categorical syllogism emerges as a venerable tool in the arsenal of reasoning. This intricate procedure unfolds its wings when two premises, bound by a common term, engage in a dance of logic, leading to a conclusion bereft of the common term. In the symphony of deductive reasoning, Aristotle’s innovation resonates with timeless significance. The exemplar, a syllogism involving Plato’s mortality, serves as a beacon illuminating the path Aristotle carved in the annals of Western logic. His contribution, an indelible mark etched on the canvas of reason, reverberates through the epochs.

7. Logic: Invented the Syllogism

In the realm of logic, Aristotle’s groundbreaking invention, the syllogism, stands as an intellectual colossus. This ingenious mechanism orchestrates the convergence of two foundational premises, conducting them through the crucible of reasoning to birth a third, distinct conclusion. A categorical architecture underpins this logical marvel, offering ten fundamental categories to articulate statements about any entity. From the intrinsic nature to its myriad attributes, relationships, and temporal dimensions, Aristotle’s logic unfolds like a masterful tapestry, capturing the complexity of existence in a symphony of reasoned thought.

- Substance or Kind

- Qualities, Traits, and Attributes

- Quantity

- Relationship to Other Things

- Placement or Location

- Time or Age

- Place

- State

- Actions or Activities

- Receptions or Effects

8. Poetics

Aristotle’s groundbreaking work, “Poetics,” dating back to approximately 335 BC, stands as a testament to the earliest surviving repository of dramatic ideas and marks the inception of philosophical discourse on literary concepts. This magnum opus represents Aristotle’s innovative foray into the realm of ποιητικῆς, denoting poetry or, more precisely, “the poetic art.” The term itself derives from the Greek word for “poet; author; maker,” ποιητής.

Within this textual tapestry, Aristotle intricately dissects the art of poetry, categorizing it into verse drama—encompassing comedy, tragedy, and the satyr play—lyric poetry, and epic. The delineation of poetic genres is further elucidated through the triad of Matter, Subjects, and Method. Aristotle’s analytical prowess extends to the identification of fundamental components within tragedy, encapsulated in Plot (mythos, hamartia), character (ethos), thought (dianoia), diction (lexis), melody (melos), and spectacle (opsis).

Delving deeper into the narrative fabric, Aristotle expounds on critical concepts like Mimesis, Hubris, Nemesis, Anagnorisis, Peripeteia, and Catharsis. These conceptual facets collectively contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the diverse elements that constitute the rich tapestry of poetic expression. The genres, united by the thread of mimesis or imitation of life, nevertheless, diverge across dimensions Aristotle meticulously outlines: the nuances of music encompassing rhythm, harmony, meter, and melody; the intrinsic quality of goodness within characters; and the mode of narrative presentation, oscillating between storytelling and theatrical enactment.

9. Immanent Realism

In philosophical lineage akin to his mentor Plato, Aristotle’s intellectual vista traverses towards the universal. Within Aristotle’s ontological framework, the universal (katholou) finds its anchorage in particulars (kath’ hekaston), tangible entities in the physical world. This starkly contrasts with Plato’s conception, where the universal assumes the form of an ideal entity that tangible objects strive to emulate. For Aristotle, the enduring significance lies in the concept of “form,” still serving as the foundational essence of phenomena but now “instantiated” in specific substances.

10. Ethics

Ethics, the profound exploration of human morality and virtue, finds its roots in the philosophical musings of Aristotle, who posited that man, as a rational animal, is inherently guided by reason. In the intricate tapestry of ethical considerations, Aristotle espoused the concept of the Golden Mean—an equilibrium that advocates moderation in all facets of life. The crux of his ethical framework revolves around the notion that the virtue of an entity is intricately tied to the correct performance, or ergon, of its essential characteristics.

Aristotle delved into the nuanced facets of human nature, asserting that each being must have a specific function germane to its essence. This function, he argued, involves the active engagement of the psuchē (soul) guided by reason (logos). Central to his ethical philosophy is the pursuit of eudaimonia—an optimum state achieved through virtuous conduct, navigating the delicate balance between the excesses and deficiencies that accompany human actions. Eudaimonia, often translated as “happiness” or “well-being,” becomes attainable only through the cultivation of an excellent character, denoted as ēthikē aretē, which manifests as moral virtue or excellence.

11. Substance

Aristotle’s profound contemplation extends to the metaphysical realm as he embarks on an exploration of substance (ousia) and essence (to ti ên einai) in his work “Metaphysics” (Book VII). In this philosophical odyssey, he unveils the concept of hylomorphism, asserting that a specific substance is an intricate amalgamation of both matter and form. This intricate interplay forms the bedrock of his metaphysical theory, wherein he distinguishes the matter of a substance as the substratum—the essential stuff from which it derives its existence. Aristotle’s conceptualization of substance transcends the physical and delves into the very essence of being.

12. Medicine

In the realm of medicine, Aristotle, with his characteristic intellectual prowess, dissects the fundamental qualities that underpin the fabric of the physical world. The Four Basic Qualities—Hot, Cold, Wet, and Dry—emerge as the elemental building blocks shaping the material universe. These qualities, Aristotle contends, are not mere descriptors but fundamental forces shaping the nature of substances. In his intricate exploration, he scrutinizes the dynamic interplay of these qualities, unraveling the tapestry of the physiological and elemental forces that govern the intricacies of the medical domain. Aristotle’s foray into medicine transcends the conventional, providing a philosophical lens through which to perceive the very essence of health and well-being.

13. Views on Women

Aristotle’s exploration of procreation unfurls a narrative where an active, ensouling masculine element breathes life into an inert, passive feminine counterpart. On this contentious ground, proponents of feminist metaphysics castigate Aristotle, brandishing accusations of misogyny and sexism. However, a nuanced examination reveals Aristotle’s acknowledgment of equality in the pursuit of happiness between women and men. In his rhetorical musings, Aristotle posits that the conduits to happiness should be accessible to both genders, dispelling a simplistic characterization of his views on women.

14. Politics

Aristotle, the revered ancient Greek philosopher, delved into the intricate fabric of societal organization in his monumental work titled “Politics.” In this magnum opus, he meticulously examined the dynamics of the city, which he considered a natural community. Aristotle intriguingly posited that the city holds a superior significance compared to the family, which, in turn, precedes the individual. This hierarchical order, he asserted, stems from the inherent necessity of the whole preceding its constituent parts—a conceptual innovation attributed to Aristotle.

The philosopher eloquently stated that “man is by nature a political animal,” asserting that rationality distinguishes humanity within the diverse animal kingdom. Aristotle envisioned politics not as a mechanical structure but rather as an organism, an interconnected system of indispensable elements, each reliant on the others for existence. His groundbreaking conception of the city as a natural entity distinguishes him as a pioneer in political thought.

15. Economics

Aristotle’s intellectual canvas expanded beyond politics, delving into the economic intricacies of communal living. While acknowledging that communal arrangements might appear advantageous for society, he astutely attributed social strife not to public property but to inherent aspects of human nature—an insightful facet of Aristotle’s intellectual repertoire.

Within his political treatise, Aristotle provided one of the earliest accounts of the origin of money. He postulated that the emergence of money was a consequence of interdependence among people, as they began importing and exporting goods. Seeking convenience, a societal consensus materialized around the exchange of intrinsically valuable and universally applicable commodities like iron or silver. Aristotle’s remarkably prescient overview of the functions of money, including the necessity for a universal standard of measurement, marked a pioneering contribution to economic thought.

16. Biology

Aristotle’s intellectual prowess extended to the realm of biology, where he stands as a pioneering natural historian. His systematic study of biology remains remarkable, even by contemporary standards. Aristotle’s contributions to psychology, comparative biology, anatomy, and physiology echo through the corridors of scientific history.

A groundbreaking figure in early theories of evolution and embryology, Aristotle dedicated two years to observing and describing the zoology of Lesbos and its surrounding seas. Notably, his observations included the Pyrrha lagoon at the heart of Lesbos. His comprehensive works on the History of Animals, Generation of Animals, Movement of Animals, and Parts of Animals were meticulously crafted from a rich tapestry of personal observations, insights from specialized individuals like beekeepers and fishermen, and sometimes less accurate accounts from foreign travelers.

The historical absence of Aristotle’s botanical works, lost over time, contrasts with the survival of two books on plants by his student Theophrastus—an inadvertent gap in the philosopher’s biological legacy. This emphasis on animals, however, does not diminish Aristotle’s enduring influence on the scientific understanding of the natural world.

17. Zoology: Unveiling the Historical Tapestry

The captivating journey of zoology unfolds through epochs, an intricate exploration of the animal kingdom that finds its roots in the ingenuity of Aristotle. While the formal consolidation of zoology as a distinct discipline occurred much later, its embryonic stages echo through the corridors of time, resonating with the organic musings of Aristotle and Galen in the ancient Greco-Roman world. These venerable scholars laid the foundation upon which the edifice of zoological sciences would eventually stand.

18. Scientific Style: The Symphony of Systematic Inquiry

In the annals of scientific exploration, Aristotle emerges as a virtuoso, wielding a distinctive style that transcends epochs. His scientific modus operandi involved the meticulous gathering of knowledge, unveiling patterns that wove through entire cohorts of animals, and deriving plausible causal explanations from this rich tapestry. This approach, akin to the symphony of systematic inquiry, mirrors the ethos of contemporary biology, especially when grappling with torrents of data in nascent fields like genomics. Though diverging from the certainties of experimental science, Aristotle’s biology unveils testable hypotheses, constructing a narrative that breathes life into observed phenomena.

19. Potentiality and Actuality: The Dance of Transformation

Delving into the realm of change and its causation, Aristotle’s profound insights, as expounded in his Physics and On Generation and Corruption, transcend the mundane. Within this intellectual labyrinth, he dissects the dynamics of transformation, categorizing it into growth and diminution (a metamorphosis in quantity), locomotion (a spatial shift), and alteration (a qualitative change). Aristotle posited that capacities, such as the art of playing the flute, could be transmuted from potentiality to actuality through deliberate cultivation. The concept of potentiality (dynamis) and actuality (entelecheia) dances intricately with matter and form, adding layers of philosophical richness to the discourse. The genesis of a property unfolds in a flux where nothing endures, and Aristotle’s astute delineation of potentiality and actuality becomes a cornerstone in understanding the essence of change.

20. Classification of living things

Aristotle distinguished about 500 species of animals, arranging these within the History of Animals in a graded scale of perfection, a scala naturae, with a man on the prime, which is one of Aristotle’s inventions. His system had eleven grades of animal, from highest potential to lowest, expressed by their type at the start: the best gave dwell start to sizzling and moist creatures, and the bottom laid chilly, dry mineral-like eggs. Animals got here above crops, and these in flip have been above minerals.

Aristotle’s Scala naturae (highest to lowest)

| Group |

Examples

(given by Aristotle) |

Blood |

Legs |

Souls

(Rational,

Sensitive,

Vegetative) |

Qualities

(Hot-Cold,

Wet–Dry) |

| Man |

Man |

with blood |

2 legs |

R, S, V |

Hot, Wet |

| Live-bearing tetrapods |

Cat, hare |

with blood |

4 legs |

S, V |

Hot, Wet |

| Cetaceans |

Dolphin, whale |

with blood |

none |

S, V |

Hot, Wet |

| Birds |

Bee-eater, nightjar |

with blood |

2 legs |

S, V |

Hot, Wet, except Dry eggs |

| Egg-laying tetrapods |

Chameleon, crocodile |

with blood |

4 legs |

S, V |

Cold, Wet except scales, eggs |

| Snakes |

Watersnake, Ottoman viper |

with blood |

none |

S, V |

Cold, Wet except scales, eggs |

| Egg-laying fishes |

Sea bass, parrotfish |

with blood |

none |

S, V |

Cold, Wet, including eggs |

(Among the egg-laying fishes):

placental selachians |

Shark, skate |

with blood |

none |

S, V |

Cold, Wet, but placenta like tetrapods |

| Crustaceans |

Shrimp, crab |

without |

many legs |

S, V |

Cold, Wet except the shell |

| Cephalopods |

Squid, octopus |

without |

tentacles |

S, V |

Cold, Wet |

| Hard-shelled animals |

Cockle, trumpet snail |

without |

none |

S, V |

Cold, Dry (mineral shell) |

| Larva-bearing insects |

Ant, cicada |

without |

6 legs |

S, V |

Cold, Dry |

| Spontaneously-generating |

Sponges, worms |

without |

none |

S, V |

Cold, Wet or Dry, from earth |

| Plants |

Fig |

without |

none |

V |

Cold, Dry |

| Minerals |

Iron |

without |

none |

none |

Cold, Dry |

He grouped what the trendy zoologist would name vertebrates as the warmer “animals with blood”, and beneath them the colder invertebrates as “animals without blood”.

Those with blood have been divided into the live-bearing (mammals), and the egg-laying (birds, reptiles, fish).

Those without blood have been bugs, crustacea (non-shelled – cephalopods, and shelled), and hard-shelled molluscs (bivalves and gastropods).

He recognized that animals didn’t precisely match right into a linear scale, and famous numerous exceptions, equivalent to that sharks had a placenta just like the tetrapods.

21. Physics – Five elements

In his On Generation and Corruption, Aristotle associated every one of the 4 components proposed earlier by Empedocles, Earth, Water, Air, and Fire, with 2 of the 4 smart qualities, sizzling, chilly, moist, and dry.

In the Empedoclean scheme, all matter was the product of the 4 components, in differing proportions. Aristotle’s scheme added the heavenly Aether, the divine substance of the heavenly spheres, stars, and planets.

Aristotle’s elements

| Element |

Hot/Cold |

Wet/Dry |

Motion |

Modern state

of matter |

| Earth |

Cold |

Dry |

Down |

Solid |

| Water |

Cold |

Wet |

Down |

Liquid |

| Air |

Hot |

Wet |

Up |

Gas |

| Fire |

Hot |

Dry |

Up |

Plasma |

| Aether |

(divine

substance) |

— |

Circular

(in heavens) |

— |

22. Motion

Aristotle, the venerable philosopher of antiquity, intricately dissects the realm of motion, unveiling a dichotomy that transcends mere physicality. In his magnum opus, the Physics (254b10), he delineates the nuanced classifications of motion, meticulously categorizing it into the realms of the “violent” or “unnatural motion” and the sublime “natural motion.” The former, akin to the trajectory of a propelled stone, is explicated as a transient force, extinguishing the moment the agent ceases to impart it. Astonishingly, Aristotle, in his profound exploration in On the Heavens (300a20), unveils the paradigm of “natural motion,” akin to the descent of an object under gravity, a revelation that stands as one of Aristotle’s intellectual bequests.

Within the realm of violent motion, Aristotle’s perspicacity illuminates a profound truth – the moment the causative force dissipates, the motion succumbs to inertia. It is a treatise of equilibrium, an ode to the intrinsic proclivity of objects to embrace a state of rest, an aspect curiously bereft of Aristotle’s musings on the perturbing influence of friction.

Delving deeper into Aristotle’s cognitive tapestry, a fascinating observation emerges – the weighty denizens of our terrestrial realm demand a more formidable force to induce motion, an astute revelation that extends to the elucidation that objects, under the propulsion of greater force, traverse their spatial confines with a swifter cadence.

23. Chance and Spontaneity

Aristotle, the sage of causality, unfurls a profound dissertation on chance and spontaneity, unraveling their intricate roles as causative agents in the cosmic tapestry. In Aristotle’s metaphysical landscape, chance and spontaneity emerge as elusive triggers, distinct from the deterministic causality inherent in simple necessity.

The incidental causality of chance, Aristotle posits, finds its dwelling amidst the capricious intricacies of accidental phenomena, emanating “from what is spontaneous.” Yet, within this categorical expanse, there exists a refined breed of chance – an ethereal entity christened “luck,” a whimsical force exclusively tethered to the moral choices of humanity. Aristotle’s intellectual odyssey unearths the subtle interplay of these forces, painting a philosophical fresco that transcends the mere happenstance of existence.

24. Optics

Aristotle, the erudite explorer of knowledge, embarks on a mesmerizing expedition into the enigmatic realm of optics. In his exploration chronicled in Problems, book 15, he unveils an apparatus that epitomizes intellectual ingenuity – a camera obscura. This obscure chamber, cloaked in darkness, harbors a minute aperture through which the ethereal luminescence permeates, a creation that stands as a testament to Aristotle’s inventive acumen.

Within this optical sanctum, Aristotle conducts experiments that border on the sublime. Regardless of the aperture’s shape, a mesmerizing constancy prevails – the solar apparition perpetually retains its circular visage. The sagacious observer, Aristotle, keenly notes that augmenting the spatial chasm between the aperture and the image surface engenders a magnification of the celestial tableau, an insight that attests to the depth of his optical discernment.

25. Four Causes

Aristotle, a luminary of ancient philosophy, introduced a groundbreaking concept suggesting that the genesis of an occurrence could be ascribed to the synergistic interplay of four distinct types of causative factors, constituting a unique facet of his intellectual legacy. The term he employed, ‘aitia,’ conventionally translated as “cause,” transcends mere temporal sequences, urging a more nuanced interpretation akin to “explanation.” This linguistic subtlety, though, shall not deter us from adhering to the conventional translation for our discourse.

Delving into Aristotle’s intellectual labyrinth, the four causes unfurl themselves as intricate strands weaving the tapestry of causality. The first, the Material Cause, encapsulates the substance or essence from which a phenomenon springs forth, embodying the very fabric of existence. The second, the Formal Cause, explores the essential structure or blueprint that defines the intrinsic nature of the entity in question. The third, the Efficient Cause, scrutinizes the dynamic processes and agents that set the wheels of causation in motion, orchestrating the unfolding drama of events. Finally, the last cause, the Telos or Final Cause, peers into the ultimate purpose or end towards which an event or entity inexorably gravitates.

26. Binomial Nomenclature

Aristotle, a virtuoso in the taxonomy of existence, etches his indelible mark on the annals of biological classification. In his magnum opus, the ‘History of Animals,’ Aristotle meticulously crafts hierarchical classifications, a choreography of life unfolding from the lowly to the sublime. At the apogee of this taxonomic ballet, he enshrines humanity.

Yet, Aristotle’s intellectual odyssey does not cease with classification; it extends into the very nomenclature of living beings. He pioneers the art of binomial nomenclature, a symphony where each organism performs a duet of identity. The first note, “gender,” resonates with familial bonds, while the second, the poignant “species,” captures the unique melody that distinguishes one organism from its kin. In Aristotle’s taxonomy, the scientific becomes harmonized with the poetic, creating a lexicon that echoes through the corridors of biological understanding.

27. Objects From Abstraction or ‘Removal’ (ta ex aphaireseôs)

In the labyrinthine corridors of Aristotle’s philosophical musings, an intriguing concept emerges Objects from Abstraction or ‘Removal’ (ta ex aphaireseôs). Aristotle, in his characteristic linguistic dexterity, occasionally designates mathematical entities as objects achieved through, within, from, or employing elimination. The multifaceted expressions, whether ‘ta aphairesei,’ ‘ta en aphairesei,’ ‘ta ex aphaireseôs,’ or ‘ta di’ aphaireseôs,’ represent a lexicon of logical discourse. This intricate linguistic dance finds its resonance in the Topics of Definitions, where the addition or subtraction of terms metamorphoses an expression, birthing intellectual revelations.

Our intellectual odyssey compels us to unravel the enigma of logical and psychological elimination, a technique Aristotle deploys to navigate four perplexing puzzles. Beginning with the realm of perceptible or physical magnitudes, Aristotle weaves a tapestry of deduction, wherein the subtraction or addition of components triggers a cascade of intellectual consequences.

28. First Scientific Treatise on Philosophy and Psychology

Aristotle, a luminary of ancient philosophy, stands as the pioneering architect of the conceptual framework for the soul in the Western philosophical tradition. In a groundbreaking departure from his predecessors, Aristotle meticulously delineated the soul as the primal force, an intrinsic power that begets life, feeling, and cognition. His magnum opus, “Of anima,” emerges as the seminal treatise wherein he crystallizes the philosophical foundations of the soul.

Within the pages of this profound work, Aristotle posited the soul not as an ephemeral abstraction but as the connective essence that binds the corporeal form to the realm of thoughts. The soul, according to Aristotle, acts as the metaphysical bridge, harmonizing the intricate interplay between the tangible body and the intangible realm of consciousness. Through this conceptual lens, Aristotle illuminated the intricate dance between matter and form, as the corporeal form constitutes the matter, and the soul, in its ethereal nature, assumes the role of the shaping form. Acqlar Agency: Marketing Tools to Monetize Videos and Animation

29. Soul: The Quintessence of Human Essence

The human soul, in Aristotle’s elaborate philosophical anatomy, emerges as a composite entity, amalgamating the potent attributes of various soul types. Much like the vegetative soul, it possesses the extraordinary capacity for self-nourishment and growth. Simultaneously, akin to the sensitive soul, the human essence harbors the remarkable ability to undergo sensations and traverse through the realms of spatial movement.

However, the true pièce de résistance lies in Aristotle’s delineation of the rational soul, a distinctive facet that elevates humanity above other living entities. This rational soul stands as an intellectual citadel, endowed with the unparalleled capability to apprehend and assimilate the diverse forms inherent in the world. The unique prowess of the human soul lies in its capacity to transcend the mundane and engage in profound cognitive processes.

At the epicenter of this cognitive prowess is the nuanced interplay of the ‘nous’ (mind) and ‘logos’ (reason). Aristotle, with a deft stroke of philosophical acumen, elucidates how the human soul, particularly the rational aspect, acts as an intellectual crucible. It not only absorbs the myriad forms encountered in the external world but, through the faculties of the mind and reason, discerns, compares, and weaves them into a coherent tapestry of understanding. The human soul, in Aristotle’s schema, becomes the quintessence of intellectual refinement, symbolizing the apotheosis of consciousness in the vast tapestry of existence. How AI, ChatGPT maximizes earnings of many people in minutes

30. Memory

Aristotle delves into the intricate domain of memory, employing the term ‘reminiscence’ to encapsulate the precise act of retaining an experience within the mind. This retention occurs within the impressions formed through sensation, accompanied by mental anxiety, a residue of the experience’s specific time and processed contents.

Memory, in Aristotle’s conceptual framework, is an entity tethered to the past, distinct from the future-oriented nature of prediction and the immediate responsiveness of sensation. The retrieval of impressions, he contends, is not an instantaneous phenomenon; rather, it necessitates a transitional channel, deeply rooted in our past experiences. This channel serves not only the purpose of recalling past experiences but also plays a pivotal role in shaping our current perceptions.

31. Dream

Aristotle, in his treatise On Sleep and Wakefulness, offers a nuanced exploration of the realm of dreams. Sleep, according to Aristotle, is a phenomenon triggered by the overuse of senses or the digestive processes, presenting an essential aspect of the body’s functionality. During the state of sleep, the fundamental cognitive activities—thinking, sensing, recalling, and remembering—transform, deviating from their wakeful manifestations.

The absence of sensory input during sleep precludes the emergence of desires, which Aristotle posits as the offspring of sensation. Despite this sensory dormancy, Aristotle notes that the senses maintain a certain degree of functionality during sleep, albeit operating in a manner distinct from wakefulness, unless fatigued. Musical Instruments. Instrumental Software. Analog and Digital Synthesizers. Combo Organs

32. Just War Theory

Aristotle’s perspective on war unfolds as a complex tapestry, revealing both admiration and caution. He lauds war as an opportunity for virtue, contending that the “leisure that accompanies peace” tends to breed arrogance in individuals. Justifying war as a means to “avoid becoming enslaved to others,” Aristotle embeds the concept of self-defense within his discourse on warfare.

Intriguingly, he posits that war, despite its tumultuous nature, has a transformative effect, compelling individuals to embrace justice and temperance. However, Aristotle introduces a paradoxical caveat — for a war to be considered just, it must be chosen with the ultimate aim of establishing peace. This nuanced perspective stands as a distinctive contribution to Aristotle’s broader philosophical framework.

More Interesting Articles